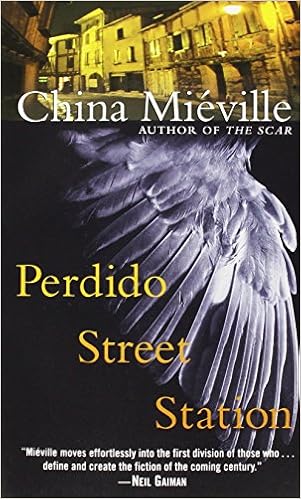

You can't get much further away than falling into one of China Miéville's worlds. The really good writers transcend their genres. Miéville's fantasies are densely detailed and wildly imagined places, fully-realized with their own culture, politics, history, and beings.

In the sprawling city of New Crobuzon humans, humanoids, cactus creatures, flying monsters, demons, dimension-spanning freaky-spider "Weavers," and AI junkyard dogs pursue their individual and intersecting destinies. It is in some ways a very familiar urban landscape, but interspersed with such mind-bendingly alien perspectives and surreal description that you'll be knocked refreshingly off your axis. It combines aspects of steampunk, action-adventure, the occult, horror, picaresque, and tragedy. As with all his novels that I've read, Perdido Street Station is highly-recommended.

Next, I returned to another of my favorite authors, Michael Chabon, and his delightful historical novel, Gentlemen of the Road (or "Jews with swords," as he likes to call it). This swashbuckling adventure is set in the Caucasus mountains in the days when warring khans ruled (around 950 AD). Two unlikely Jewish bandits have partnered up, finding themselves embroiled in a fight to restore a young prince to his rightful throne, which has been usurped by a treacherous villain who wiped out his entire family. It is action-packed and sparkles with Chabon's signature wit and memorable characters.

Next, I returned to another of my favorite authors, Michael Chabon, and his delightful historical novel, Gentlemen of the Road (or "Jews with swords," as he likes to call it). This swashbuckling adventure is set in the Caucasus mountains in the days when warring khans ruled (around 950 AD). Two unlikely Jewish bandits have partnered up, finding themselves embroiled in a fight to restore a young prince to his rightful throne, which has been usurped by a treacherous villain who wiped out his entire family. It is action-packed and sparkles with Chabon's signature wit and memorable characters. My all-around literary balm for whatever is ailing me is Shakespeare. I got to see A Comedy of Errors in the place it premiered in 1594 (!) while in London -- the Hall of Gray's Inn. It was farcical and bubbly, given a screwball-comedy vibe by the musically-inclined cast of the Antic Disposition Company. At home, I'll be seeing Macbeth and Titus Andronicus this month, and meanwhile, I just started James Shapiro's The Year of Lear, which is fantastic so far. I'm learning so much about the writing of Lear. Very cool.

My all-around literary balm for whatever is ailing me is Shakespeare. I got to see A Comedy of Errors in the place it premiered in 1594 (!) while in London -- the Hall of Gray's Inn. It was farcical and bubbly, given a screwball-comedy vibe by the musically-inclined cast of the Antic Disposition Company. At home, I'll be seeing Macbeth and Titus Andronicus this month, and meanwhile, I just started James Shapiro's The Year of Lear, which is fantastic so far. I'm learning so much about the writing of Lear. Very cool.I hope you find your own great escapes. Try to get as far away as possible.